Collaboration is for losers

France offers a lesson, and hope, in the fight against an authoritarian

One of the things that gives me hope for America is a small room just inside the entrance to L’Hotel de Ville, Rennes’ 18th-century city hall whose tower rises above the rooftops in this 2,000-year-old town. It’s known as the Pantheon, though it’s not nearly as magnificent as the one you’d see in Paris.

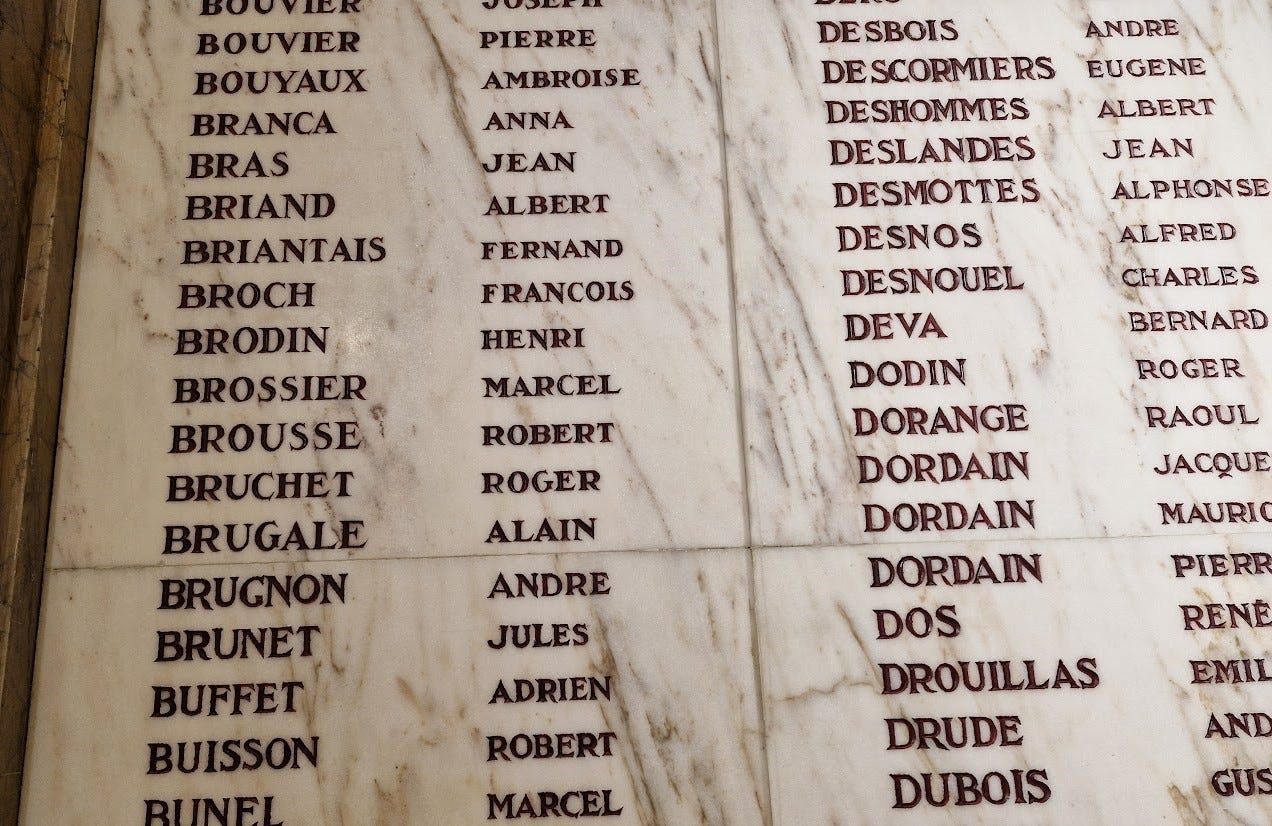

Its walls are covered with marble tablets engraved with the names of Rennes’ citizens who died for France, starting with World War I. The plaques continue with names from World War II, and onto armed conflicts in Southeast Asia, North Africa, Afghanistan and elsewhere. They are topped by a 26-meter-long hand-painted frieze of soldiers on the battlefield.

The floor, a ceramic mosaic by renowned Italian artist Isidore Odorico, is spectacular, but never pulls your eyes from the names, each a permanent reminder of sacrifice.

The lighting is dim, and the space is usually empty, so its pair of padded benches make a good place for contemplation.

As your eyes drift across the names, they rise upward to the ceiling, to the bold names of France’s military leaders in World War I.

FOCH, JOFFRE, PAU…

One name you won’t see is PETAIN, and that is what gives me hope.

For Philippe Pétain was, after the first World War, among of the Republic’s greatest heroes, “the Savior of France” for his leadership at the Battle of Verdun, the Marshal of France, the nation’s highest military distinction. Rennes once renamed the square outside of City Hall – the central point in our city – Place Philippe Pétain.

His name in this room is covered with a discreet panel.

The reason, of course, is Pétain was the head of France’s authoritarian government headquartered in Vichy after the nation fell to Germany in 1940. While he remained a beloved leader through the early years of Nazi occupation (many French held out hope he had a secret plan to turn the tables on Germany), he ultimately fell from grace because of Vichy’s policy of “collaboration.” Established by law, collaboration secured Hitler’s authority without a fight, while enriching the Axis with French resources and labor, and dooming tens of thousands of French Jews and others to prison, deportation and execution.

Moreover, it thoroughly undermined France’s long tradition of democratic values. Vichy even dropped the republic’s promise of Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité, replacing it with the motto, Travail, Famille, Patrie (Work, Family, Fatherland). “Real liberty,” Pétain pontificated, “cannot be exercised except under the shelter of a guiding authority, which they [citizens] must respect, which they must obey…”

While Pétain assured the defeated nation he was ushering in a new, glorious era for France, it is a photograph of Pétain shaking hands with Hitler that is the lasting image of the former hero. At the end of the war he was convicted of treason and spent the rest of his life under arrest on one of those forgotten French islands where they dispatch criminals and deposed dictators.

So, in the end, the autocrat who sided with a foreign dictator over the best interests of his nation got what was coming to him.

But that alone is not what gives me hope.

Because collaboration was not just a governmental policy. It was also a social phenomenon that took all sorts of nefarious forms – some that I see repeating themselves in troubling fashion in America today.

Private citizens formed their own militia, the French Legion of Volunteers Against Bolshevism, to fight with the Germans. They took an oath to Hitler, cast their arms upward in the Nazi salute, and eventually joined the Waffen-SS.

Companies competed with each other to curry Hitler’s favor. They willingly did business with their occupiers, supplying everything from wine to photography equipment. Automaker Louis Renault, for example, rebuilt his Paris factory after it was destroyed by Allied bombing, so that he could continue repairing German tanks. (He was convicted of collaboration and died in prison.)

The pro-Nazi media exposed Resistance cells and called for the murder of politicians who opposed Hitler. The nation’s largest-circulation newspaper in the occupied zone, Je Suis Partout (I Am Everywhere), railed that “We must separate from the Jews as a whole and not keep the little ones.” (Not for nothing, its 35-year-old editor was executed even before France was liberated, for sharing intelligence with the enemy.)

Though collaborationists among the French never represented a very large number – perhaps two percent of the population, according to one official count – the phenomenon took hold because most people just didn’t care. They were tired of fighting after World War I and, frankly, many looked down at Jewish people with unvarnished disdain. Moreover, they held Pétain – well into his 80s with little experience as a political leader when he took control of the Vichy government – in high regard, despite his facist leanings and other obvious faults.

So things turned dark. The French ratted on their neighbors. French police chased down Jews. French elected officials passed laws to carry out the Führer’s demands.

It took years for outright opposition to gather steam.

But the good news – and the hope I’m left with after a visit to Rennes’ Pantheon – is that it eventually did.

It started with small-scale acts of resistance. Shopkeepers pretended to not understand German-speaking troops who patronized their businesses. Kids scrawled “V” for victory signs in dust on car windshields. One of my favorite stories is of the teenager who’d ride his bicycle down the streets of Paris, whistling the opening notes of Beethoven’s Fifth, da–da–da-dum, which corresponds with the Morse code for the letter V. Parisians would lean out of their windows and whistle it back to him.

Still others published pamphlets, including one called Conseils à L’Occupé (Advice to the Occupied), that importantly reminded readers:

CE NE SONT PAS DES TOURISTES. Ils sont vainqueurs. (These are not tourists. They are conquerors.)

After the war, French people would recall these small acts as important signs that they were not alone in their opposition to les Boches.

Anti-Nazi sentiment would eventually grow stronger, and the resistance would take the form of more direct action, including sabotage. One of the first serious acts in Rennes took place a couple months after the Germans stormed into the city, when a 31-year-old man named Marcel Brossier cut some telephone cables running to a military installation. He was quickly caught and executed.

By all accounts, Brossier was hardly a hero. He had no family, he never served in the military (a portion of his leg had been amputated as a youngster), he once spent two months in prison for stealing a bicycle while drunk. His remains were placed in a common grave.

And, yet, etched into the marble of the Pantheon in Rennes – in the room where Phillipe Pétain’s name can no longer be found – is the name of Marcel Brossier, Mort pour la France.

That is who we remember. A lone individual who stood up to authoritarianism. And that is what gives me hope.

Note: I am not a military historian. If you spot a factual error, please let me know so I can correct it!

Things are bleak here. Apparently conservatives believe executive orders trump federal law and even the Constitution. Anyone in the federal government not deemed sufficiently loyal is bring fired.

I just started reading Sinclair Lewis' "It Can't Happen Here" written in the 30s about a demagogue elected president who beomes a dictator. The patallels with Trump are chilling. For example, the Trump character is a powerful politician who is also head of a privarely raised militia. When the guy is arrested and charged with graft, his militia followers rise up and take control of the state capitol and office buildings while forcing the people who arrested him to leave the state. A successful January 6.

Trump will go down in history with the Joe McCarthys and Father Coughlins as a disgrace. But he'll do a lot of damage first. - Jim Heenehan

Excellent piece. During WW II, France was a nation at war with itself. Who among friends, family or neighbors were collaborators; who were the resistance; who were just trying to keep their heads down below the radar and feed their families?

When we first came to France in the 70s, WW II was still raw and memories fresh. We met people slightly older than us who had experienced the war at ground level. Here in Brittany, the Resistance was particularly strong. In the Battle for Brittany in '44, the Shelborne Resistance Line evacuated shot-down British airmen from Bonaparte Beach near the town of Plouha, just a half hour from our house. We were there a couple days ago. You can walk the Shelborne Trail from Plouha down to the beach in the steps of French Underground heros who led over 300 British aviators to boats offshore waiting to bring them back home.

I can't listen to Leonard Cohen's song "The Partisan" without feeling a strong emotion.

The parallels to the US today are still being written. Similar to France in WW II, America is currently at war with itself. I wonder who the "Partisans" of today will be. The Resistance is already forming among people I know. Will America come to its senses? The jury is out.