Off With Their Heads

A slice-of-life look back at the National Razor, from Marie Antoinette to David Bowie

Lately, there have been musings from America about importing that most French of judicial appurtenances, the long-gone guillotine. As in: Say what you will about the croissant-eaters, but back in the day they had a pretty good idea about how to deal with rich bastards and dictators.

Ah, yes, le rasoir national — the very symbol of the French Revolution, when public beheadings were a crowd-pleasing national pastime. Never mind that those dark days are deservedly branded as the Reign of Terror; Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette had it coming and, well, desperate measures for desperate times (hint, hint).

The idea, as I’m sure you’re aware, was that the device was a humanitarian means of expediting one’s departure from these surly bonds. A clean break, as it were. How clean, no one was ever certain, as those with first-hand experience were generally mute on the matter. A German scientist of the late 18th century (why is it always a German scientist?) tried to put the question to rest by conducting tests on severed heads. One experiment, as recounted by researcher Matthew D. Turner, involved tweaking a freshly exposed spinal cord “to elucidate grimaces from the beheaded face.” (Herr Doktor, later expressing regret for taking part in the experiment, estimated that the “life force” present in the head lasted for up to 15 minutes.)

And so, with the pain issue unsettled, the French continued using the guillotine until 1977. You read that right. They were lopping heads off over here as recently as when “Laverne & Shirley” were on TV.

I feel a bit squeamish knowing that I’m living in a country where the chopping block was used for more than just celery. But also intrigued. I wondered about its use here in Rennes.

We had our share of prunings. There was the guy who beat and drowned his father, with the help of his mother. (She got only 20 years of forced labor.) There was the French maid who poisoned three dozen victims in the mid-1800s.

Most of those who went tête-a-tête with the guillotine in town were terminated during the aforementioned Reign of Terror, when an estimated 330 locals lost their noggins. Despite the device’s reputation as a means of settling scores with the rich, its most frequent victims were peasants and artisans, not noblemen. Murder was not a prerequisite; you just needed to be accused of being an enemy of the Revolution. Two women, for example, were decapitated for the crime of hiding a priest who had refused to take an oath of loyalty to the state. (The priest got the guillotine, too.)

The whole bloody mess was directed by local military tribunals under the direction of Jean-Baptiste Carrier, a sick dude described by one historian as "one of those inferior and violent spirits, who in the excitement of civil wars become monsters of cruelty and extravagance." Before you say that sounds like a certain member of the Trump administration, know that Carrier was w-a-y worse. Among other things, he was the guy behind the so-called Nantes Drownings, when more than 4,000 suspected royalists were sent to the bottom of the Loire.

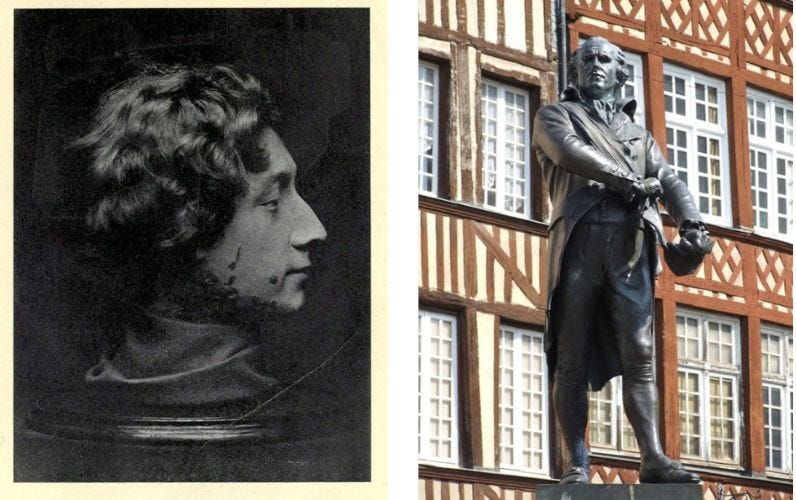

In Rennes, the city’s newspapers advertised executions and cheering crowds turned out as the slicer was set up in front of the Parliament Palace. Our good mayor Jean Leperdit eventually put the kibosh on the bloody mess, famously ripping up a list of locals whom Carrier had ordered beheaded.

Both men received appropriate tributes. The city erected a statue of Leperdit and his famous list. Madame Tussaud made a wax model of Carrier’s severed head.

I’ll stick my neck out and argue that the city’s most notable go-round with the guillotine was its last, on February 4, 1939. Not because of the criminal; he was a common thief named Maurice Pilorge who murdered his accomplice in nearby Dinard.

What made the beheading so remarkable was the executioner: Anatole Deibler.

Born in Rennes, Deibler had been overseeing public beheadings across France for 54 years. His father had held the job for 40 years before that, and his grandfather before him. Go ahead, you can say it: They were blood relatives.

This guy was an international celebrity. A glowing 1936 profile of Deibler in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that “he has a hypnotic power in his eyes which calms the terror-stricken criminal about to be executed.” He dispatched his victims professionally and flawlessly — except once, the newspaper reported, when a severed head began talking after it had fallen into the basket. “Tell Deibler to straighten his cravat!” the bodiless head reproved. Deibler nearly lost his shit. A hack reporter for Le Matin de Paris later revealed he’d hired a ventriloquist for the stunt.

On the morning of the Pilorge execution, Deibler packed up his portable mincing machine and headed to Gare Montparnasse for the train to Rennes. This was to be his career 300th beheading — the kind of achievement that would earn one a bust in the Guillotine Hall of Fame, if there were such a thing.

Alas, it was not to be. While waiting on the Metro platform, Deibler keeled over with a massive heart attack and died on the spot.

Pilorge earned a stay of execution while the executioner’s office settled on a replacement. Two days later, they dragged him to his destiny at the front gate of our Jacques-Cartier Prison. He was wearing a dunce’s cap, a cigarette dangled from his mouth. It would be the guillotine’s last appearance in Rennes, which would be the end of this story, except…

It turns out the French poet Jean Genet, who also spent time in prison for petty crime and lewd acts, was fixated on the killer. Though the two never met, Genet dedicated his first novel, “Our Lady of Flowers,” to Pilorge, calling him “a murderer so handsome that he makes the day pale.”

I’ve never read the novel, so I can’t speak to its worth. But its influence is indisputable. Jean-Paul Sartre regarded it as a triumph of existentialism. Divine, the outrageous drag queen of “Pink Flamingos” fame, was named after the book’s main character. And many years later, David Bowie, a fan of the novel, would nod to Genet with the driving lyrics of one of his best songs:

He’s outrageous.

He screams and he bawls

Jean Genie let yourself go

Don't lose your head! A guillotine-inspired expression used figuratively since the early 19th century.

Based on a vague memory, I checked and verified that this slicing machine was used in Germany by the Nazis to dispatch around 5000 enemies of the state, including the White Rose group who led resistance in Munich to Hitler.

Thanks to Google, I also ran across a guillotine recommended to be used to dispatch rodents after their use in scientific experiments - a mini-guillotine that you can buy online.

And now I'm getting guillotine ads on Facebook. Don't tell Stephen Miller!

Very interesting, although the part about the experiments made me a bit queasy. It led me to look up the last execution in Rodez -- April 1936 and Deibler arrived from Paris to do the slicing. The previous one had been in 1910, after a murder committed right in our village! I had no idea.